Helping Kids to Be Who They Were Made To Be — and Growing Up Ourselves in the Process

Note: This post is written especially from my perspective as a parent, but I think the teachers and college students who read it will find some good stuff here too. For Black History Month I’ll also be adding brief bios of amazing people and events you might not have heard about (I am a historian, after all, how could I resist?)

I’d love to know what you think. Leave a comment at the bottom of this post or shoot me an email.

I’ve been thinking a lot lately about how I can encourage my kids to be who they were made to be—which I believe will lead to their personal happiness as well as making the world a better place.

I’ve also been thinking about how easily we parents (and teachers) can miss seeing what our kids are meant to be and do—and what support they need from us—because of the way we are influenced by our own blind spots, beliefs, fears, wounds and unfollowed dreams.

Often there can be aspects of the broader culture and communities we live in that make it hard for us to see our kids as they are and as they are meant to be, too. Ideas that we breathe in like air. Ideas about race, religion, gender, and class; ideas about professions and jobs, about who can and should be expected to do what—and who can’t and shouldn’t.

There’s plenty of research that demonstrates that unconscious biases impact what we see and do in relation to children.

They cause preschool teachers to think that Black boys are more disruptive than they actually are, for example, resulting in high numbers of preschool expulsions. And those preschool expulsions have real, long-term impacts on the lives of those boys.

Unconscious biases can also cause us to miss opportunities to nurture gifts in our children. We might notice and nurture the leadership potential, or the math prowess, or the athletic skills in our sons, but not think to do the same for our daughters. We might miss these opportunities even if we say that girls can be and do anything they want.

Unconscious beliefs and the actions that follow them aren’t intended to be harmful, but that doesn’t prevent a negative impact on kids’ lives.

Our conscious biases, hopes and values can trip us up too. We might believe strongly that artists can’t make a good living, and that boys who are artists will have a hard time socially. We might think artists live wild, immoral or irresponsible lives. We don’t want our kids to experience that kind of pain or struggle. So, we might avoid nurturing that spark in our children, or even actively dissuade them from exploring a career in the arts.

Sometimes we might miss the mark just because our kids are so different from us that we have no idea how to support them—that’s me when it comes to all team sports!

At the moment, I have a fifteen-year-old and a twenty-year-old. Two boys.

The twenty-year-old gave us a rough time his junior year in high school. Blew apart all that I thought I knew—about him, about good parenting, about who God is. I am so thankful for that year, for the way he called me and his dad to grow up and show up in ways that we needed to. But it was painful.

If you’re in the midst of a year like that (or several)—whether it’s with a teenager, or an infant, or a child in between—I can certainly empathize. And I encourage you to get all the help you can—therapy, coaching, prayer, massage, yoga. Whatever you need. Strip out every other responsibility you think you must to do (but really, if you’re honest the world would keep spinning if you let it go for a while) and care for yourself.

Why? So you can show up for your kid in all those crazy hard ways s/he needs you to, and at those inconvenient times when your first thought is, “I really can’t handle this right now!”

Like at two o’clock in the morning,

Or after the hardest day you’ve ever had at work, or the loneliest day you’ve ever had at home.

You can do it, but not on your own.

Kids are so good at teaching us what we need to really grow up and become the strongest (and happiest!) version of ourselves that we can be . . . if we lean into the lessons.

Looking back on that year with my son, I think part of what happened with us was that we (his dad and I) weren’t really seeing him.

We had a picture of who he was—and who he should be—and we saw that, but not him. Not who he was at that time:

- A kid who no longer believed in the religious doctrines we’d taught him and needed the freedom to talk about it without the focus of the conversation being on us persuading him to see things our way;

- A kid who needed his parents to challenge him to do things he didn’t want to try that we were pretty sure he’d like. Even though it made him angry.

- A kid whose parents were strong enough to let him hate us for a while and even to believe that we hated him when in fact we loved him so much our hearts were breaking with grief over the distance between us.

- A kid who was involved in a whole lot of stuff we didn’t think he’d even thought about.

- And years before it all blew up, he had been a kid who needed us to see how he was hurting and how much he needed us to intervene even though he seemed so independent and self-sufficient and always said he was fine. We believed him, because it was easier for us to believe him, but not because we really saw him.

I don’t think we were terrible parents, but I can see some places where we really missed the boat with him. And in the process of working through that – and forgiving ourselves and moving forward — we’ve developed a relationship with our young adult son that is pretty awesome!

Very few parenting (or teaching) mistakes are irredeemable. We can always start where we are.

But still, I’d like to do better with my younger son. I’d like to really see him – even when he can’t see himself fully just yet. And if you have a teenager you know that they don’t always make it easy!

So, this month I’m going to do some reading and thinking and reflecting with these questions in mind:

- How can we adults, educators and parents especially, help our kids to become who they are meant to be?

- How can we begin to see hints of what that is and give them the tools they need to get there?

And if you’re in that one-quarter-kid/three-quarters-adult phase that is college life, I’ll be thinking about you too. Giving you ideas for how you can start to follow your own guidance as you move out to make your own way in the world, even when what you notice is different from your parents’ ideas for you.

That's what my older son is doing now. And boy is it fun to watch!

Personally, I’m going to start with curiosity about my younger son.

I’m going to keep my mouth shut for a week and just observe without making suggestions about what he should/shouldn’t be doing to find his way in the world.

I’m going to pretend that I don’t know this kid who keeps showing up at my house for food.

I might ask him a few questions—the “what were your highs and lows today?” one is always a good one. But mostly I’m going to observe. And I’m going to ask for some Divine wisdom, for “eyes to see.”

Of course, I’ll still do the usual parenting tasks of making sure he’s doing the chores and homework we already agreed on. But this week he’s not going to hear from me about how he watches too much TV or doesn’t read enough or practice basketball enough or how since we now live in Los Angeles he should learn to surf or to speak Spanish or take an improv class.

Maybe I won’t notice anything new. Maybe I will. I’ll let you know.

If you don’t have a kid at home, try it with a challenging student—or a quiet, compliant one.

Or do the same kind of observation with yourself as the subject. Take a week off from telling yourself what you are supposed to like/be/do . . . and see what you notice.

Experiment with me?

Here’s to thriving!

Deb

Did You Know?

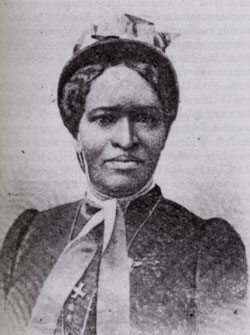

Born in slavery in 1837, Ms. Amanda Berry Smith was a leader and a trail blazer in many ares of life—as a woman, and educator, and as an African American. After being widowed twice and working as a domestic servant for many years, she began a career as a preacher, gospel singer, missionary and educator. From 1870-78, she performed around the U.S., and also in Great Britain and other European countries, singing at Christian "camp meetings" to mostly white audiences, then lived in India and Liberia as a missionary from 1879-1890. When she returned to the United States, she opened an orphanage and school in Harvey, Illinois, near Chicago, one of the earliest of its kind. She was also active in various social movements, working alongside Black and White national leaders including Ida B. Wells and Frances E. Willard. Amanda Berry Smith wrote and published her autobiography in 1899, making her one of the first African American women to become a published author. She died in 1915, soon after which (sadly) her school was burned to the ground in a suspicious fire.